Her Majesty Queen Victoria

Alexandrina Victoria, 1819–1901, Queen of Great Britain and Ireland (1837–1901) and Empress of India (1876–1901). She was born in Kensington Palace in London on May 24th, 1819 and the only child of Edward, duke of Kent ( fourth son of George III ), and Princess Mary Louise Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld.

Early Reign

Victoria's father died before she was a year old. Upon the death (1830) of George IV, she was recognized as heir to the British throne, and in 1837, at the age of 18, she succeeded her uncle, William IV, to the throne. With the accession of a woman, the connection between the English and Hanoverian thrones ceased in accordance with the Salic law of Hanover. One of the young queen's advisers was Baron Stockmar, sent by her uncle, King Leopold I of the Belgians.

Her first prime minister, Viscount Melbourne, became her close friend and adviser. In 1839, when Melbourne's Whig cabinet resigned, Victoria refused to dismiss her Whig ladies of the bedchamber, the accepted gesture of confidence in the incoming party. The Tory leader, Sir Robert Peel, declined to form a cabinet, and Melbourne remained in office.

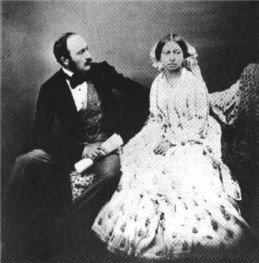

Marriage to Prince Albert

In 1840, Victoria married her first cousin, Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha. Albert, with whom she was very much in love, became the dominant influence in her life. Her first child, Victoria, later empress of Germany, was born in 1840, and the prince of Wales, later Edward VII, in 1841. Victoria had nine children. Their marriages and those of her grandchildren allied the British royal house with those of Russia, Germany, Greece, Denmark, Romania, and several of the German states.

Through Albert's efforts, Victoria was reconciled with the Tories, and she became very fond of Peel during his second ministry (1841–46). She was less happy with the Whig ministry that followed, taking particular exception to the adventurous foreign policy of Viscount Palmerston. The resulting friction was a factor in Palmerston's dismissal from office in 1851. The queen and Albert also influenced the formation of Lord Aberdeen's coalition government in 1852. Royal popularity was increased by the success of the Crystal Palace exposition (1851), planned and carried through by Albert.

It began to wane again, however, when it was rumored on the eve of the Crimean War that the royal couple was pro-Russian. After the outbreak (1854) of the war, Victoria took part in the organization of relief for the wounded and instituted the Victoria Cross for bravery. She also reconciled herself to Palmerston, who became prime minister in 1855 and proved a vigorous war leader.

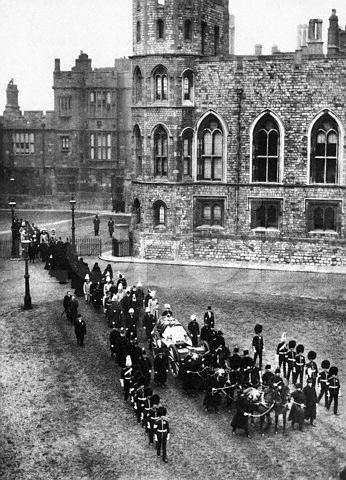

Widowhood and Later Years

In 1861, Albert (who had been named prince consort in 1857) died. Victoria's grief was so great that she did not appear in public for three years and did not open Parliament until 1866; her prolonged seclusion damaged her popularity. Her reappearance was largely the work of Benjamin Disraeli, who, together with William Gladstone, dominated the politics of the latter part of Victoria's reign.

Disraeli, adroit in his personal relations with Victoria, became the queen's great favorite. In 1876 he secured for her the title empress of India, which pleased her greatly; she was ardently imperialistic and intensely interested in the welfare of her colonial subjects, particularly the Indians. Victoria's relations with Gladstone, on the other hand, were very stiff; she disliked him personally and disapproved of many of his policies, especially Irish Home Rule.

In her old age, Victoria was enormously popular. Jubilees were held in 1887 and 1897 to celebrate the 50th and 60th years of the longest English reign. The queen was not highly intelligent, but her conscientiousness and strict morals helped to restore the prestige of the crown and to establish it as a symbol of public service and imperial unity.

2520victoria.jpg30.2 KB · Views: 924

2520victoria.jpg30.2 KB · Views: 924 image002__2_.jpg9.4 KB · Views: 3,989

image002__2_.jpg9.4 KB · Views: 3,989 Q_Vic.jpg10.9 KB · Views: 3,837

Q_Vic.jpg10.9 KB · Views: 3,837 1842.jpg15.8 KB · Views: 3,922

1842.jpg15.8 KB · Views: 3,922 1.jpg27.2 KB · Views: 3,907

1.jpg27.2 KB · Views: 3,907 QV1.jpg15.1 KB · Views: 4,304

QV1.jpg15.1 KB · Views: 4,304 vanda_1.jpg21.4 KB · Views: 4,615

vanda_1.jpg21.4 KB · Views: 4,615 queen_vic.jpg29.7 KB · Views: 3,937

queen_vic.jpg29.7 KB · Views: 3,937 vic2.gif31 KB · Views: 3,850

vic2.gif31 KB · Views: 3,850 vicreg.jpg25.3 KB · Views: 4,332

vicreg.jpg25.3 KB · Views: 4,332