Interview

Hello friends,

This is an interview given by Her Majesty to some paper. I think is interesting to read it and I want to point out her sincerity talking about so difficult things.

Enjoy it.

February 11, 2005

February 11, 2005

Farah Diba Pahlavi, the deposed Empress of Iran, lives alone in a vast, dazzlingly tasteful apartment overlooking the River Seine. The floors are scattered with fine silk rugs, the tables with Persian antiquities, and handmade bon-bons are offered by a silent maid in a starched pinafore.

``Exile is very hard,'' says the empress, sinking into a soft armchair. She has had 25 years of it. The early ones spent as an international pariah, the later ones as a retreating echo of a tumultuous but long-passed time.

Now, says Farah, her huge brown eyes focused on the middle distance, she can finally scent the prospect of a homecoming. Iran, she believes, is changing fast. The Islamic radicals who drove out her late husband, the Shah, are on borrowed time.

Soon, says Farah, the demand for democracy, bubbling up in a restless young population that has known little but rule-by-Mullah will become irresistible. The backwash from Iraq's elections will roll unstoppably across the border. And then what she calls the ``black parenthesis'' in her ancient nation's otherwise distinguished history will end, and she will be free to return.

In his State of the Union address last week, US President George W Bush came close to saying America will back moves to topple Iran's regime, now apparently intent on acquiring nuclear weapons.

US Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice voiced a similar line on her visit to London: ``The Iranian people should have a chance to determine their own future.'' Would such a future include rolling out the welcome mat for the ex-empress?

Farah evidently likes to think so. In her memoir, An Enduring Love: My Life with the Shah, she more or less says so. The book, which is just about to come out in paperback, adoringly portrays the Shah - a man of disturbing opinions whose reign was as corrupt and repressive as that of any Third World martinet - as one of the great statesmen of history, a ruler of saintly benevolence and unchallengeable wisdom, who brought prosperity, modernity and emancipation to his country.

The torture and murder routinely practised by Savak, the Shah's secret police, is dismissed with the literary equivalent of a wave of the hand, ``Some Savak agents no doubt went too far and it is said committed indefensible acts.''

There is a lot about ``how cruel history is'' and how ``unfair'' it has been, but surprisingly little introspection or analysis. Whatever the Iranians think of the mullahs, which, as Farah rightly says, isn't much, there appears little to suggest that they want the Pahlavis back. ``It would be a decision for the people, of course,'' she says in a low, throaty voice that owes its rasp to a lifetime's smoking. ``Nothing could happen without their agreement.''

Farah expresses high hopes of her eldest son, the 44-year-old, self-styled Reza II, who, from a base near Washington DC, runs a pro-democracy Iranian exile group.

``I believe,'' she says, ``that he can be a unifying factor, in the way that monarchies are.''

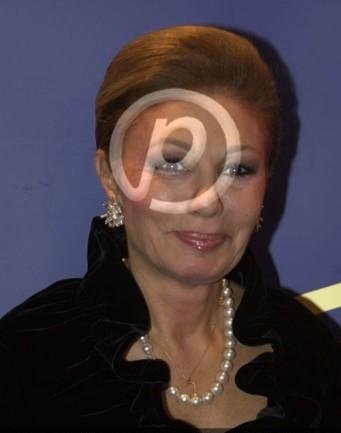

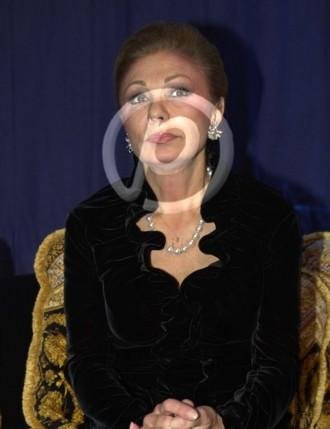

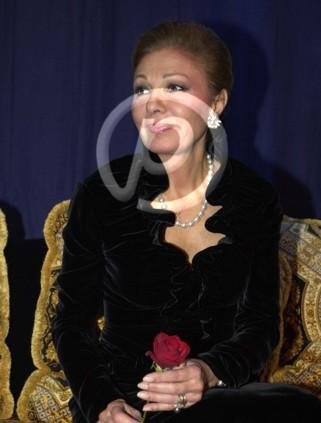

At 66, Farah remains eye-catchingly elegant, in a well-cut charcoal trouser suit and lethally pointed shoes. Her hair is pulled back in a sweeping coif, and the Nefertiti-like eye make-up that was once her trademark - in the days when she was portrayed by Andy Warhol - is more delicately applied.

She has never remarried, and when I ask her why not she looks faintly shocked and says, ``The memory of my husband is still so alive in me. I feel always so attached to him. Also, I feel that I am married to my destiny and my country, and so I have never felt the necessity or the wish.''

Every year, the empress visits her husband's tomb in the Al-Rifai mosque in northern Cairo. She remembers him ``as a civilised man. He was caring, he was a good husband and I never once heard him raise his voice or show anger.''

He was also, according to accounts written by less sympathetic hands, a great philanderer, with a distinctly old-fashioned line on the limits of women's abilities, whose quips included, ``In a man's life, women count only if they are beautiful, graceful and know how to stay feminine. Women have never produced a Michelangelo or a Bach or even a great cook.''

Farah was certainly beautiful, graceful and feminine - and scarcely out of her teens - when she caught the Shah's eye. Born into a well-connected Teheran family, she was studying architecture in Paris when she met the twice-married, but conspicuously heirless Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi at a reception. The Shah, 39, had divorced his first wife, Princess Fawzia, the sister of King Farouk of Egypt, after she produced only a daughter, and his second wife, Soraya Esfandiari Bakhtiari, when they failed to have any children.

Just 10 months after her wedding, in 1960, Farah gave birth to Reza. A honor guard fired a 21-gun salute as the birth was announced, and, recalls Farah, ``people were dancing in the streets.''

Before long, the streets were also hosting less propitious displays of public feeling. The powerful Islamic establishment took a dim view of what it considered to be the Shah's decadent, pro-Western posturing, and when he announced a program of agrarian reform that would strip thousands of imans of their traditional land titles, opposition took root in earnest.

The Shah, in the shape of his dreaded secret police, took a ruthless approach to dissent, and behind the glossy veneer of the ``new modern Iran'', an ugly, slow-burning stand-off developed.

In January 1979, with Iran paralysed by strikes and mass protests, the Shah and Farah fled into exile. No country expressed an eagerness to take them, and after short, fraught stays in the Bahamas, Mexico and Panama, among other places, they were finally allowed to settle in Egypt where the Shah died, 18 months later, of leukemia.