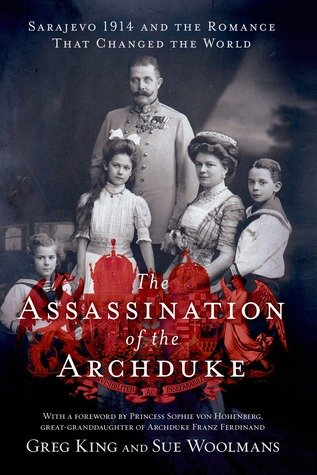

"The Assassination of the Archduke"

blogcritics.org

Life can be unpredictable and is often infused with bitter irony. Consider the incredible and terrible course of the two brothers Ernst and Max. Born into the luxury of the Austro-Hungarian imperial family — their father was next in line to the imperial throne — the two ended up in Dachau concentration camp.

Their fate is the most shocking aspect of The Assassination of the Archduke. But the story of their fate is, of course, deeply intertwined with a far greater and violent episode of European history, the decline and the destruction of Austria-Hungary, most visibly announced by the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand, their father.

June 28, 2014 will mark the 100th anniversary of that fateful day. The tide of years, of course, has erased most everything of that time except for the buildings and a handful of individuals who can claim direct lineage to the families of Imperial times. One of these sentries of the past called Konipiste or Konopischt, a chateau located about 50 miles from Prague, where the Archduke and his Countess spent a few happy years, is now the object of a decade old legal fight between a descendant Sophie von Hohenberg and the Czech government. With the passing of time, certain aspects of the past may also be forgotten. This is certainly the case with respect to the personal lives of the Archduke and the Countess as much of the history of that time focuses on the larger issues of politics in an attempt to divine the causes of the Great War, a project which does not easily admit the personal.

The Assassination of the Archduke works to reverse this and reveals the human story of the Archduke Ferdinand, his problematic marriage to Countess Chotek, their problems at Austrian imperial court, their moments of happiness at Konopischt, their death in Sarajevo and the fate of their children as their world unraveled around them.

The Assassination of the Archduke creates a compelling and readable account of the private life of the imperial family headed for doom.

Archduke Ferdinand wasn’t to be emperor, but the death of his cousin and Crown Prince Rudolf and the abdication by his own father made him the only heir to the imperial throne. From the very first, the Emperor Franz Joseph I disliked the Archduke. Their relationship was further complicated when Ferdinand chose a woman who could never be Empress, the Countess Sophie Chotek, as his wife.

The morganatic marriage proved to be a source of great friction at the imperial court. The Emperor viewed it and the reformist ideas of the Archduke as proof of his unsuitability as future Emperor. For example, the Archduke at one point became convinced that Austria-Hungary could survive only after becoming radically reformed along the lines of a federal union similar in structure to the United States of America, an idea that the Emperor though preposterous and dangerous.

Not a few historians believe that choices could have been made differently and that the Great War ultimately avoided. But the character of Franz Joseph I that comes across in this book casts doubt on such naive views: The Emperor was incapable of change — moreover, he hated the idea of reform. How do you convince such a man to act against his beliefs and interests? It would require nothing less than magic to change the old Emperor into a man capable of finding common ground with the Archduke and entertain notions of reform. In this sense, the Great War was impossible to avoid because the people who were responsible for making it happen could not possibly alter their thinking. The possibility of choice, then, is an illusion created by hindsight. The decisions that were made were the only decisions that could ever have been made given who the people involved in the situations were as people.

As the years wore on, however, The Emperor’s attitude softened somewhat. Countess Chotek was elevated in her station. But some hings could never change: neither she nor her two sons could ever be part of the imperial family. Then, when the Archduke and his wife were killed in Sarajevo, Franz Joseph I breathed a sigh of relief. His hopes for preserving the old order seemed about to be assured. But it was not to be: precisely a month, on July 28, war erupted that would sweep his empire away.

Ultimately, a deep irony obtains from the story of the Archduke Ferdinand: though disliked by Emperor Franz Joseph I, the Archduke Ferdinand through his assassination was the direct cause of the decision by Austria-Hungary to attack Serbia, which caused the European continent to descend into war that destroyed three empires of Germany, Russia and Austria-Hungary [Four empires, including the Ottoman]. Even in death, Ferdinand remade Austria-Hungary in a fundamental way but not in the way he planned or imagined. And the old Emperor was unable to prevent the destruction of tradition he valued so much.

[FONT="]

[/FONT]