Day in History: Battle of Stamford Bridge

1066 is nowadays remembered as the year of the Norman Invasion of England, but it could have as easily been the Norwegian invasion.

The death of the childless Edward the Confessor triggered a succession crisis as there was no clear-cut heir to the Throne. At some point, it was believed he would be succeeded by Edmund Ironside’s son, Edward Aetheling. And indeed, the King ensured the young heir returned to England (he was raised in Hungary), possibly with the view of proclaiming him the heir. Unfortunately, the young man died almost immediately upon his return in 1057. He did leave a son behind, Edgar, who was also given the designation Aetheling (meaning throneworthy); however, while the boy might have initially been considered a potential successor, towards the end of Edward the Confessor’s reign he had no supporters or political power. The likeliest candidates for the Throne of England were Harold Godwinson, William the Bastard and Harald Hardrada.

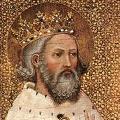

Harold Godwinson was Edward the Confessor’s brother-in-law. Edward was married to Edith of Wessex, Harold’s sister and the daughter of Godwin, Earl of Wessex. The Godwin family was easily the most powerful of English lords. Towards the end of Edward’s reign, the Godwin brothers controlled all of England apart from Mercia. Harold’s claim was thus based not as much on actual succession rights (although he was a direct descendant of King Aethelwulf), but the fact he already did de facto controll most of the country. And indeed, as soon as Edward the Confessor was dead, Harold was proclaimed King and promptly crowned. It is argued that he was actually the first King of England to have been crowned in Westminster Abbey; however, since the first monarch to have definitely been crowned there was Harold’s successor, William the Conqueror, the honour of having been the first is usually attributed to him.

The second claimant was William, Duke of Normandy. His claims were likewise not based on succession rights, but the fact Edward the Confessor had promised to name him his heir. William of Normandy and Edward the Confessor were second cousins once removed; their relation, however, came not through Anglo-Saxon Royal Houses but through Emma of Normandy who was William’s great aunt (Emma was the sister of William’s grandfather, Richard II of Normandy) and Edward’s mother. Edward’s promise to William, if it did ever take place, was verbal and not supported by any kind of treaties. According to William of Poitiers (a well-known supporter of William), Edward the Confessor sent Harold Godwinson to Normandy in 1064 to re-confirm his promise to William. According to the same source, shortly after his accession to the Throne Harold himself sent an envoy to William, admitting Edward the Confessor did make such promise; however, Harold supposedly argued that this was overridden by Edward’s deathbed similar promise to Harold. William didn’t dispute the supposed deathbed promise, but claimed that Edward’s prior promise took precedence over the latter one.

The third and final claimant was Harald Hardrada, King of Norway. He based his claim on an agreement made between Magnus I of Norway and Harthacnut in 1038, which stated that if either died, the other would inherit the deceased’s throne and lands. Harthacnut had succeeded his father, Canute the Great, as King of England. When he died, the Throne of England was inherited by his maternal half-brother (the son of Emma of Normandy and her first husband, Aethelred the Unready), in violation of the aforementioned treaty. Since Edward had effectively been Harthacnut’s co-ruler (possibly, along with their mother), as well as the son and heir of the previous Anglo-Saxon Monarch, his Kingship was virtually undisputed within the country. Magnus did mind what he viewed an usurpation, but his intention to invade England was thwarted by Sweyn Estridsson’s uprising in Denmark. Upon Edward’s death, Harald was quick to remind of the treaty; he argued that since Edward left no descendants, there could be no other legitimate heir but himself. Harald also found a somewhat surprising ally, Tostig Godwinson, Harold Godwinson’s brother, who supported Harald in his attempted invasion.

Harold Godwinson knew an invasion attempt was imminent, but he expected William, Duke of Normandy to be the first to attack. To counter that, he stationed his hastily-assembled army in Southern England to meet the Norman invaders; yet months went by, and William’s troops made attempts to land in England. Unfortunately for the Anglo-Saxons, Harald Hardrada was the first to attack; the King of Norway saw his opportunity, believing there was no way the Anglo-Saxon army (stationed in the other end of the country) would manage to arrive in time to thwart his invasion. He was wrong.

As soon as Harold learnt of the Norwegian invasion, he headed north at great speed with his houscarls and as many thegns as he could gather, travelling day and night. It is said that Hardrada’s messenger told Harold that the Norse King had come to conquer all of England. Harold supposedly replied: “I will give him just six feet of English soil; or, since they say he is a tall man, I will give him seven feet!” The journey from London to Yorkshire, a distance of 185 miles, was covered in mere four days: the Norwegians remained unaware of the enemy’s arrival until they actually saw them. The sight of the English army caught them completely by surprise as they weren’t expected the Anglo-Saxons for another week: they were unprepared, with about 1/3 of their army still on the ships.

The armies met near the Stamford Bridge on 25 September 1066. Harold’s soldiers were made up of housecarls and the fyrd. Housecarls were well-trained, full-time soldiers who were paid for their services but the fyrd were working men who were called up to fight for the king in times of danger. King Harold’s army was exhausted but determined; the Norwegians were well-rested but taken by surprise. Nevertheless, the unexpected arrival of the English army definitely gave them a huge advantage. The Norwegian army was divided in two with little to no communication between them. Most of the warriors had also left their armour and some of the weapons behind at their ships, courtesy of unreasonably warm September day. Before the Vikings even understood what was happening, the bulk of their army on the west side of the river was annihilated.

Crossing the river appeared to have posed some problems for the English though: a folklore story (backed by several contemporary sources) has it that a giant Norse warrior armed with a Dane Axe blocked the narrow crossing and single-handedly held up the entire English army. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle states that this Viking managed to slay up to 40 Englishmen and, despite his many wounds, was somehow holding on the passageway. He was only defeated when an English soldier floated under the bridge in a half-barrel and thrust his spear through the laths in the bridge, mortally wounding the brave man.

This heroic deed was not in vain, however; his sacrifice allowed most of the surviving Norse army from the west bank to join the rest of the army and form a shieldwall to face the English attack. Once the English did cross the bridge, they locked shields and attacked. The battle raged for many hours but ultimately the Norse army’s ill-thought decision to leave their armour behind cost them the battle. Their army began to fragment, allowing the English troops to force their way in and break up the Scandinavians’ shield wall. The Norse army was further demoralised when their King, Harald Hardrada, was killed.

At this point, the Norse army received one more chance when the troops that had been left behind to guard the ships arrived, led by Eystein Orri, the fiancé of Hardrada’s daughter Ingegerd. Knowing their comrades were in grave danger, they had arrived in such a hurry that some of Orri’s men collapsed and died of exhaustion upon arrival. The remaining soldiers were, however, fully armed and ready for the battle. Their counter-attack, described as “Orri’s Storm”, turned the tables for a while and halted the English advance. Unfortunately, too many Vikings had already died and Orri’s troops were too heavily outnumbered. Orri was slain and the Norse army was crushed. It is said that so many died in such a small area that decades after the battle, the field was still whitened with bleached bones of Norwegians and Anglo-Saxons who perished there.

The victorious English army accepted a truce with the surviving Norwegians, including Harald’s son Olaf. They were allowed to leave after giving pledges not to attack England ever again. The losses suffered by the Norse army were so horrific that they needed only 24 ships to carry the survivors away – and that from a fleet of over 300 ships. It is estimated that over 2/3 of the Norwegians perished in the battlefield. Although several battles between the English and Norse forces would take place in later decades, the Battle of Stamford Bridge is traditionally considered to be the end of Norwegian domination in the British Isles. Unfortunately, it soon turned out to be the beginning of the end of the Anglo-Saxon world.

The battle of Stamford Bridge was a decisive victory for the English King. It proved him to be an able commander and the English troops, particularly the Housecarls, to be well trained, highly skilled and capable of great endurance. The Anglo-Saxon didn’t have a lot of time to celebrate the glorious victory though; only three days later, on 28 September, they received news the Normans under the command of William, Duke of Normandy had finally landed on the south coast of England. Harold Godwinson was then forced to rush his battered and tired forces to the other end of the country. The English and Norman armies met at the Battle of Hastings, on 14 October 1066; in spite of all the disadvantages, the Anglo-Saxons fought a great battle and had chances to win or at the very least, not to be defeated. Fate would have it the other way though; Harold was killed, the English army was defeated and the Anglo-Saxon era ended.

The significance of the Battle of Stamford Bridge is immense; had Harold not been forced to leave William’s landing on the south coast unopposed, and then face him with an army that had suffered significant losses, was ill-prepared and weary, then the outcome may have been very different. Certainly, his initial position in the south of the country (before he received news on the Norwegian invasion) was an advantageous one and could have well stopped the Norman invasion before it even started. In addition, Harold’s exhausted forces had covered over 350 miles in a very short time and fought off another invasion; they were too tired to fight to the best of their abilities. Of the long-term consequences, the most devastating one for the Saxons was the fact that so many thegns, noblemen and leaders died at the Battles of Stamford Bridge and Hastings, that it was virtually impossible for the Anglo-Saxons to resist the Norman lords: quite simply no leaders of note remained to rally around.

To read more about the Saxon and Danish Kings, visit this thread – The Saxon and Danish Kings of England and their Consorts.

Filed under Historical Royals, Norway, The United KingdomTagged Army, Battle of Hastings, Battle of Stamford Bridge, Edward the Confessor, Emma of Normandy, Harald III Sigurdsson of Norway, Harold Godwinson, Military, William the Conqueror.

Leave a Reply