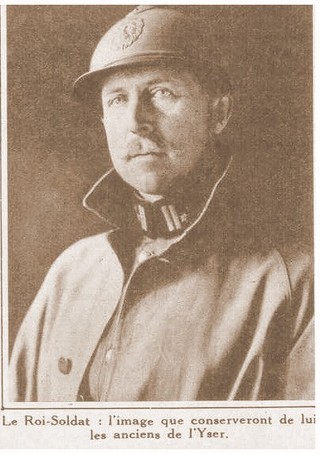

Death of the Soldier King

Seventy-five years ago, on 17 February 1934, King Albert I of Belgium fell off the Roche du Vieux Bon Dieu, at Marches-Les-Dames, while mountaineering. He did not survive his fall, and, as quickly as that, Belgium lost its third King.

King Albert I was the second son of Prince Philippe, Count of Flanders and brother of King Leopold II, and Princess Marie of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen. Albert was not meant to become King – he was more the “spare” heir. After the death of his cousin, Prince Leopold, his older brother Baudouin was trained to follow in his uncle’s footsteps. The young Prince was very popular, so when he died unexpectedly, Prince Albert suddenly had very big footsteps to fill at the early age of 16.

King Albert I was the second son of Prince Philippe, Count of Flanders and brother of King Leopold II, and Princess Marie of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen. Albert was not meant to become King – he was more the “spare” heir. After the death of his cousin, Prince Leopold, his older brother Baudouin was trained to follow in his uncle’s footsteps. The young Prince was very popular, so when he died unexpectedly, Prince Albert suddenly had very big footsteps to fill at the early age of 16.

Albert was a studious young man, and rather quiet by nature. He was very concerned with the well-being of his people. He is known to have travelled incognito to the poor, working-class neighbourhoods in Belgium, to see with his own eyes the conditions in which his people had to live. He also travelled through the Belgian Congo, and upon his return he formulated many recommendations to improve living conditions there. Later, he would be famous for his reform efforts, which include trying to implement universal suffrage and make the University of Ghent a Flemish university (where before, university lessons had always been in French).

In 1909, upon the death of King Leopold II, Albert became the new King of the Belgians. He was the first to take the oath in both (Flemish) Dutch and (Walloon) French, which he both spoke fluently. At the time of his accession to the throne, many had their doubts about Albert’s capabilities as King. However, soon it was clear that he was not a man to be messed around with. King Albert’s early reign was remarkable for the many institutional reforms he had implemented in the Belgian Congo. And, of course, there was The War…

At the beginning of World War I, the Germans asked for passage through Belgium to attack France. One of Belgium’s key reasons for existing was, in fact, that it constituted a buffer zone between the mighty powers of the end of the Nineteenth century: Germany, France and Great Britain. The answer of King Albert was brave as well as audacious: “I rule a nation, not a road.” With this, the King knew he had entered the war, which would signal the end of an era. When the German troops prepared to invade Belgium, the King went to Parliament and asked permission to take over command over the army, which was granted. And then, the nation was pleased to see King Albert really was a leader. He stayed with his troops, fought with them, inspired them to continue the fight, no matter how hopeless it all looked. He made his sons fight along with him, which was a morale boost to no end for the Belgian army. He did not send his wife, Queen Elisabeth, to the safety of England either, but encouraged her to roam the army hospitals and help the injured soldiers. And thanks to the bravery and perseverance of the Belgian troops, France and Britain, the actual targets of the First World War, had time to organize their armies for the Battle of the Marne.

At the beginning of World War I, the Germans asked for passage through Belgium to attack France. One of Belgium’s key reasons for existing was, in fact, that it constituted a buffer zone between the mighty powers of the end of the Nineteenth century: Germany, France and Great Britain. The answer of King Albert was brave as well as audacious: “I rule a nation, not a road.” With this, the King knew he had entered the war, which would signal the end of an era. When the German troops prepared to invade Belgium, the King went to Parliament and asked permission to take over command over the army, which was granted. And then, the nation was pleased to see King Albert really was a leader. He stayed with his troops, fought with them, inspired them to continue the fight, no matter how hopeless it all looked. He made his sons fight along with him, which was a morale boost to no end for the Belgian army. He did not send his wife, Queen Elisabeth, to the safety of England either, but encouraged her to roam the army hospitals and help the injured soldiers. And thanks to the bravery and perseverance of the Belgian troops, France and Britain, the actual targets of the First World War, had time to organize their armies for the Battle of the Marne.

Albert, however, soon realized his people were suffering terribly under the German occupation, at the other side of the Yser. He tried very hard to work out a diplomatic solution to the international conflict, based on the principle of ‘no victors, no vanquished’, but neither the Entente nor the Germans were favourable to the idea. Later, Albert tried to work out a treaty with the Germans, which should restore Belgium’s independence, but of course the Germans were not very willing to release the territory they had gained. It is ironic that a man remembered mostly for being a military leader was, in reality, much more inclined to find diplomatic solutions.

At the end of the war, Albert himself led the offensive which liberated Belgium from the Germans. He was welcomed in Brussels as a national hero. A legend was born.

His death, almost fifteen years later, came a shock. The King, who was an expert mountaineer, fell down a rocky ravine while he was climbing alone. When they found him, he had already died. Soon after his accident, whispers arose suggesting his death might not have been an accident, but these rumours were firmly contradicted by the Court. Albert I was succeeded by his son, Leopold III.

Tagged Albert I of Belgium, Anniversary, Biography, Death.

Leave a Reply